Portuguese nautical science

Portuguese nautical science evolved from the successive expeditions and experience of the Portuguese pilots. It led to a fairly rapid evolution, creating an elite of astronomers, navigators, mathematicians and cartographers. Among them stood Pedro Nunes with studies on how to determine latitude by the stars, and João de Castro, who made important observations of magnetic declination over the entire route around Africa.

Ships

Until the 15th century, the Portuguese were limited to cabotage navigation using barques and barinels (ancient cargo vessels used in the Mediterranean). These boats were small and fragile, with only one mast with a fixed quadrangular sail and did not have the capabilities to overcome the navigational difficulties associated with southward oceanic exploration, as the strong winds, shoals and strong ocean currents easily overwhelmed their abilities. They are associated with the earliest discoveries, such as the Madeira Islands, the Azores, the Canaries, and to the early exploration of the northwest African coast as far south as Arguim in the current Mauritania.

The ship that truly launched the first phase of the Portuguese discoveries along the African coast was the caravel, a development based on existing fishing boats. They were agile and easier to navigate, with a tonnage of 50 to 160 tons and 1 to 3 masts, with lateen triangular sails allowing luffing. The caravel's limited capacity for cargo and crew were its main drawbacks, but these did not hinder its success. Among the famous caravels are Berrio, which was the first ship of Vasco da Gama's first armada to reach Portugal after the voyage, and Anunciação (Nossa Senhora da Anunciação), which sailed with Cabral in 1500.

With the start of long oceanic sailing, larger ships were also developed. "Nau" was the Portuguese archaic synonym for any large ship, primarily merchant ships. Due to the piracy that plagued the coasts, they began to be used in the navy and were provided with cannon ports, which led to the classification of "naus" according to the power of the ship's artillery. They were also adapted to the increasing maritime trade: from 200 tons capacity in the 15th century to 500 tons later, they become impressive in the 16th century, having usually two decks, fighting castles fore and aft, and two to four masts with overlapping sails. In voyages to India in the sixteenth century, carracks were also used. These were large merchant ships with a high edge (freeboard) and three masts with square sails, which often reached 2000 tons.

In the thirteenth century celestial navigation was already known, guided by the sun position. For celestial navigation the Portuguese, like other Europeans, used Arab navigation tools, like the astrolabe and quadrant, which they made easier and simpler. They also created the cross-staff, or cane of Jacob, for measuring at sea the height of the sun and other stars. The Southern Cross become a reference upon arrival in the Southern hemisphere by João de Santarém and Pedro Escobar in 1471, starting the use of this constellation in celestial navigation. But the results varied throughout the year, which required corrections.

To this the Portuguese used the astronomical tables (Ephemeris), precious tools for oceanic navigation, which experienced a remarkable diffusion in the fifteenth century. These tables revolutionized navigation, allowing mariners to calculate their latitude. Vasco da Gama and Pedro Álvares Cabral used the tables of the Almanach Perpetuum by astronomer Abraham Zacuto, which were published in Leiria in 1496, along with his improved astrolabe.

Sailing techniques

gyre

gyre

gyre

Ocean

gyre

Pacific

gyre

Pacific

gyre

gyre

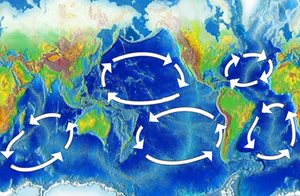

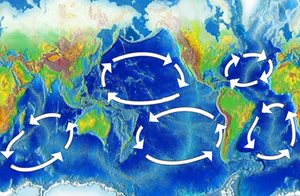

Besides coastal exploration, Portuguese also made trips off in the ocean to gather meteorological and oceanographic information (in these trips were discovered the archipelagos of Madeira and the Azores, and the Sargasso Sea). The knowledge of wind patterns and currents – the trade winds and the oceanic gyres in the Atlantic, and the determination of latitude led to the discovery of the best ocean route back from Africa: crossing the Central Atlantic to the latitude of the Azores, using the permanent favorable winds and currents that spin clockwise in the Northern Hemisphere because of atmospheric circulation and the Coriolis effect, facilitating the way to Lisbon and thus enabling the Portuguese to venture increasingly farther from shore, the maneuver that became known as "Volta do mar". In 1565, application of this principle in the Pacific Ocean led to the Spanish discovery of the Manila Galleon trade route between Mexico and the Philippines.

Cartography

It is thought that Jehuda Cresques, son of the Catalan cartographer Abraham Cresques has been one of the notable cartographers at the service of Prince Henry. However, the oldest signed Portuguese sea chart is a Portolan made by Pedro Reinel in 1485 representing Western Europe and parts of Africa, reflecting the explorations made by Diogo Cão. Reinel was also author of the first nautical chart known with an indication of latitudes in 1504 and the first representation of a Wind rose.

With his son, cartographer Jorge Reinel and Lopo Homem, they participated in the making of the atlas known as "Lopo Homem-Reinés Atlas" or "Miller Atlas", in 1519. They were considered the best cartographers of their time, with Emperor Charles V wanting them to work for him. In 1517 King Manuel I of Portugal handed Lopo Homem a charter giving him the privilege to certify and amend all compass needles in vessels.

In the third phase of the former Portuguese nautical cartography, characterized by the abandonment of the influence of Ptolemy's representation of the East and more accuracy in the representation of lands and continents, stands out Fernão Vaz Dourado (Goa ~ 1520 – ~ 1580), giving him a reputation as one of the best cartographers of the time. Many of his charts are large scale.

See also

- Iberian ship development, 1400–1600

- Iberian nautical sciences, 1400–1600

- Iberian cartography, 1400–1600

- List_of_Portuguese_inventions_and_discoveries#Nautical_science

References

- Albuquerque, Fernando (1983). Ciência e Experiência nos Descobrimentos Portugueses. Biblioteca Breve. Lisboa: Instituto de Cultura e Língua Portuguesa.

- CORTESÃO, Armando. History of Portuguese Cartography. Coimbra: Junta de Investigações do Ultramar, 1969-1971 (2 v.)

- CORTESÃO, Armando. Contribution of the portuguese to Scientific Navigation and Cartography. Coimbra: Junta de Investigações Científicas do Ultramar, 1974. 30p.

- CORTESÃO, Armando; MOTA, Avelino Teixeira da. Portugaliae Monumenta Cartographica. Lisboa: Imprensa Nacional-Casa da Moeda, 1987. 6 v. + 1 v. (mapas).

- v

- t

- e

North Africa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Sub-Saharan Africa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Middle East [Persian Gulf] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

South Asia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

East Asia and Oceania | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

North America & North Atlantic | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||

South America & Caribbean | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||