Bolzano–Weierstrass theorem

In mathematics, specifically in real analysis, the Bolzano–Weierstrass theorem, named after Bernard Bolzano and Karl Weierstrass, is a fundamental result about convergence in a finite-dimensional Euclidean space . The theorem states that each infinite bounded sequence in has a convergent subsequence.[1] An equivalent formulation is that a subset of is sequentially compact if and only if it is closed and bounded.[2] The theorem is sometimes called the sequential compactness theorem.[3]

History and significance

The Bolzano–Weierstrass theorem is named after mathematicians Bernard Bolzano and Karl Weierstrass. It was actually first proved by Bolzano in 1817 as a lemma in the proof of the intermediate value theorem. Some fifty years later the result was identified as significant in its own right, and proved again by Weierstrass. It has since become an essential theorem of analysis.

Proof

First we prove the theorem for (set of all real numbers), in which case the ordering on can be put to good use. Indeed, we have the following result:

Lemma: Every infinite sequence in has an infinite monotone subsequence (a subsequence that is either non-decreasing or non-increasing).

Proof[4]: Let us call a positive integer-valued index of a sequence a "peak" of the sequence when for every . Suppose first that the sequence has infinitely many peaks, which means there is a subsequence with the following indices and the following terms . So, the infinite sequence in has a monotone (non-increasing) subsequence, which is . But suppose now that there are only finitely many peaks, let be the final peak if one exists (let otherwise) and let the first index of a new subsequence be set to . Then is not a peak, since comes after the final peak, which implies the existence of with and . Again, comes after the final peak, hence there is an where with . Repeating this process leads to an infinite non-decreasing subsequence , thereby proving that every infinite sequence in has a monotone subsequence.

Now suppose one has a bounded sequence in ; by the lemma proven above there exists a monotone subsequence, likewise also bounded. It follows from the monotone convergence theorem that this subsequence converges.

Finally, the general case (), can be reduced to the case of as follows: given a bounded sequence in , the sequence of first coordinates is a bounded real sequence, hence it has a convergent subsequence. One can then extract a sub-subsequence on which the second coordinates converge, and so on, until in the end we have passed from the original sequence to a subsequence times—which is still a subsequence of the original sequence—on which each coordinate sequence converges, hence the subsequence itself is convergent.

Alternative proof

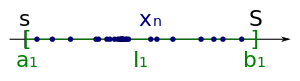

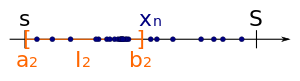

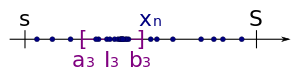

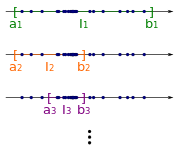

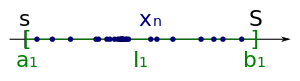

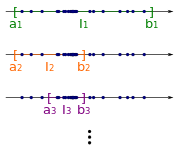

There is also an alternative proof of the Bolzano–Weierstrass theorem using nested intervals. We start with a bounded sequence :

-

Because is bounded, this sequence has a lower bound and an upper bound .

Because is bounded, this sequence has a lower bound and an upper bound . -

We take as the first interval for the sequence of nested intervals.

We take as the first interval for the sequence of nested intervals. -

Then we split at the mid into two equally sized subintervals.

Then we split at the mid into two equally sized subintervals. -

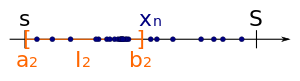

Because each sequence has infinitely many members, there must be (at least) one of these subintervals that contains infinitely many members of . We take this subinterval as the second interval of the sequence of nested intervals.

Because each sequence has infinitely many members, there must be (at least) one of these subintervals that contains infinitely many members of . We take this subinterval as the second interval of the sequence of nested intervals. -

Then we split again at the mid into two equally sized subintervals.

Then we split again at the mid into two equally sized subintervals. -

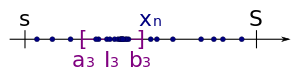

Again, one of these subintervals contains infinitely many members of . We take this subinterval as the third subinterval of the sequence of nested intervals.

Again, one of these subintervals contains infinitely many members of . We take this subinterval as the third subinterval of the sequence of nested intervals. -

We continue this process infinitely many times. Thus we get a sequence of nested intervals.

We continue this process infinitely many times. Thus we get a sequence of nested intervals.

Because we halve the length of an interval at each step, the limit of the interval's length is zero. Also, by the nested intervals theorem, which states that if each is a closed and bounded interval, say

with

then under the assumption of nesting, the intersection of the is not empty. Thus there is a number that is in each interval . Now we show, that is an accumulation point of .

Take a neighbourhood of . Because the length of the intervals converges to zero, there is an interval that is a subset of . Because contains by construction infinitely many members of and , also contains infinitely many members of . This proves that is an accumulation point of . Thus, there is a subsequence of that converges to .

Sequential compactness in Euclidean spaces

Definition: A set is sequentially compact if every sequence in has a convergent subsequence converging to an element of .

Theorem: is sequentially compact if and only if is closed and bounded.

Proof: (sequential compactness implies closed and bounded)

Suppose is a subset of with the property that every sequence in has a subsequence converging to an element of . Then must be bounded, since otherwise the following unbounded sequence can be constructed. For every , define to be any arbitrary point such that . Then, every subsequence of is unbounded and therefore not convergent. Moreover, must be closed, since any limit point of , which has a sequence of points in converging to itself, must also lie in .

Proof: (closed and bounded implies sequential compactness)

Since is bounded, any sequence is also bounded. From the Bolzano-Weierstrass theorem, contains a subsequence converging to some point . Since is a limit point of and is a closed set, must be an element of .

Thus the subsets of for which every sequence in A has a subsequence converging to an element of – i.e., the subsets that are sequentially compact in the subspace topology – are precisely the closed and bounded subsets.

This form of the theorem makes especially clear the analogy to the Heine–Borel theorem, which asserts that a subset of is compact if and only if it is closed and bounded. In fact, general topology tells us that a metrizable space is compact if and only if it is sequentially compact, so that the Bolzano–Weierstrass and Heine–Borel theorems are essentially the same.

Application to economics

There are different important equilibrium concepts in economics, the proofs of the existence of which often require variations of the Bolzano–Weierstrass theorem. One example is the existence of a Pareto efficient allocation. An allocation is a matrix of consumption bundles for agents in an economy, and an allocation is Pareto efficient if no change can be made to it that makes no agent worse off and at least one agent better off (here rows of the allocation matrix must be rankable by a preference relation). The Bolzano–Weierstrass theorem allows one to prove that if the set of allocations is compact and non-empty, then the system has a Pareto-efficient allocation.

See also

- Sequentially compact space

- Heine–Borel theorem

- Completeness of the real numbers

- Ekeland's variational principle

Notes

References

- Bartle, Robert G.; Sherbert, Donald R. (2000). Introduction to Real Analysis (3rd ed.). New York: J. Wiley. ISBN 9780471321484.

- Fitzpatrick, Patrick M. (2006). Advanced Calculus (2nd ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson Brooks/Cole. ISBN 0-534-37603-7.

External links

- "Bolzano-Weierstrass theorem", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press, 2001 [1994]

- A proof of the Bolzano–Weierstrass theorem

- PlanetMath: proof of Bolzano–Weierstrass Theorem

- The Bolzano-Weierstrass Rap

![{\displaystyle I_{1}=[s,S]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/58be63fbf6d3dff28ca6747569a558d5af61740e)

![{\displaystyle I_{n}=[a_{n},\,b_{n}]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/7d87f6f5ae37e6fb5ecb4ab2d9c16e5275221650)